Woman At Point Zero by Nawal El Saadawi - Review

Review and discussion of the text in constant production, and reflection of its content of patriarchal abuse, and intersection of gender, sex, and class

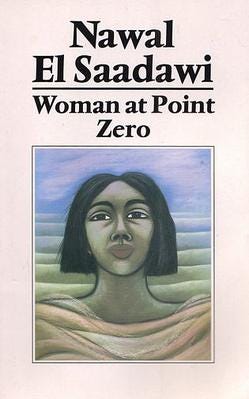

Woman at Point Zero by Nawal El Saadawi, published in Arabic in 1977, translated to English in 1983.

Woman at Point Zero has been on my wish-list for a long time now. As are many books, really, so that’s not saying a lot. I was browsing Kinokuniya, stumbled across it, and didn’t hesitate— I read it within 2 days. (This is a very short book, and I am a very slow reader).

El Saadawi trained as a doctor in Cairo, and after she was removed from her position at the Ministry of Health for upsetting the status quo with her critical publication Woman and Sex, she continued her own research by seeing women who suffered from ‘neurosis’. While researching within a prison, El Saadawi met Firdaus, who she determined was a woman unlike any other.

“I developed a feeling and admiration for this woman who seemed to me so exceptional in the world of women to which I was accustomed” (El Saadawi, p. xxv).

Something about this deduction made me wary. Well, one needs some solid proof for such hefty praise— and by the end of the book, I was convinced.

Woman At Point Zero is Firdaus’ story, as El Saadawi recollects it. Firdaus, born into poverty and having no family support, gains her secondary school certificate but inevitably can find no work with it and becomes a prostitute; her life is a downward spiral from her birth. As we know from the start, she winds up in prison, sentenced to death for killing a man.

This story is extremely easy to read. Short sentences, simple diction, and it flows quickly, which makes sense— it is Firdaus’ speech to El Saadawi, her life story gathered into the tight space before her execution. You can expect that the story is not perfectly accurate, that aspects of it have been obviously crafted (such as the parallel loves that I’ll expound on much later). In certain places I found the narration lacking, too simplistic, and wondered if it was a result of the translation— not being able to read Arabic, I can’t determine that for myself. Overall, it is an anxious, grim, compelling story.

What El Saadawi achieves with Firdaus’ story is an absolute symbol of wrath, personal autonomy, and the crisis of gender oppression faced by women, that hits the gut.

The following contains quotes and plot instances that may be spoiling, so please keep that in mind if you want to read on.

Text in constant production / the relevance of class, sex, and criticism

Let’s think about the text as being in constant production, as Julia Kristeva theorised in her semianalysis. The book has been written, translated, published, but its circulation continues, as does the impact and thoughts it will provoke— it is in constant production. Woman at Point Zero will enter anyone’s hands in any circumstance at all. In the 2024 Foreword by Selma Dabbagh, she writes that at the time of her reading this story in the early 90s, her response was “strongly conflicted and quite negative”. She tells us that, as an Anglo-Palestinian expatriate, she was living in Cairo and felt defensive of the city; her view was romanticised, and the “grim and irredeemable” landscape of patriarchal oppression was hard to reconcile with her perspective.

But the book made her “vigilant”. Dabbagh would come to see that this oppression was all around her, had always been, and she’d merely accepted these systemic workings as a given. She states, poignantly: “I took my freedoms for granted, only remarking on them when they were thwarted in some way.”

This book entered my hands just the other day in a Kinokuniya in Sydney, Australia. I’d scoured those shelves enough times to be sure it hadn’t been there for long: it was a new print. When I finished the story, my feelings were warmer than Dabbagh’s had been, but I come to it from an entirely different set of circumstances. Of course, I reflected on my own self; I’ve lived thus far in a female body, been treated as female by others, and I thought to myself, in the final pages, I’ve been lucky.

I did not, once, read Firdaus’ person as being separate from my own. I followed her narrative footsteps with the distance only a reader can have, and a reader from Western society at that (because that is a distance that must be noted), but with the intimacy, the shared body of the woman. I thought I have been lucky. Because while I have grown up in a country with better gender equality than is depicted in Egypt, women here, in Australia, still die frequently at the hands of their husbands, their abusers, the men in their lives. On the rare occasion they die at the hands of a stranger, but if you do a little probing, you’ll likely find that hatred of women was still a distinct cause. According to an ABC report as of July 1, 38 women have been murdered by men in 2024.

This feeling that I have been lucky in my life, I think is even something El Saadawi herself felt after she heard Firdaus’ story; I sense this from the final page:

“Inside me was a feeling of shame.” (p.126)

And so, Woman at Point Zero continues to produce itself in this way. It still feels relevant, no matter how different Firdaus’ specific circumstances are from your own— whether it’s that you don’t live in Cairo, or you didn’t grow up in poverty, or you have the support and protection of your family— if you know anything at all about the world we live in, you know it remains relevant. Men, as well, should be able to take notice of this.

Firdaus herself remains a spiritual force of self-preserving violence. I’m specifically not saying feminine violence. Firdaus was never a person who slotted into her assigned gender role as though it was water off her back; to be assigned the gender of woman is, in a way, forced upon you. Its deep unfairness steered Firdaus’ life until she reached a point where violence was not a question— the question, rather, was why she hadn’t thought of it sooner.

“Now you can believe that I have slapped you. Burying a knife in your neck is just as easy and requires exactly the same movement.” (El Saadawi, p. 120).

Fear, she reflects, is what had held her back for so many years but reaching that ultimate point of self-preservation made her realise she had a total and utter power over men that had been kept from her. Fear, or the propensity to feel fear, is not sexed. How you behave while feeling fear, however, is gendered: it is taught to you through social construction.

It was this ultimate revelation, I suspect, that really made her face her death with total readiness. Like she’d finally come to an action and consequence in her life that actually made sense to her. Never would she compromise on her strength again. Death was Firdaus embracing that strength.

It’s important to note that some Arab critics have criticised this book for perpetuating stereotypes of Arab-Islamic abuse against women. As Amal Amireh says in her 2000 reception study, “Some have concluded that the popularity of her novels has less to do with their literary merit than with their fulfillment of Western readers' assumptions about Arab men and women” (p.232). This is incredibly valid. El Saadawi wasn’t at all the first Arab critic of sexism and women’s oppression in Egypt— there were, indeed, many others— but her palatability in Western society has made her rather prominent, and easily misappropriated. According to Amireh’s study, El Saadawi’s criticism of women’s oppression has been used by Western feminist critics to vilify Arab society, with particular emphasis on female genital mutilation. El Saadawi’s own experience with clitoridectomy at the age of 6 has been highlighted and overemphasised in comparison to her critical focus of other related issues.

“In one interview soon after the [1980 UN-sponsored Copenhagen conference], she criticizes Western feminist attendees for their ignorance of third-world women's concerns and for their focus on issues of sexuality and patriarchy in isolation from issues of class and colonialism.” (Amireh, p.220).

I would argue that it is not the fault of El Saadawi how a story is received in other place and time contexts. It’s on the reader to do a little more legwork. If a reader from the West is not thinking with intention, it is all too easy to absorb content in a way that fits into already-modelled stereotypes one has unconsciously collected. I mean, just think about circumcision: it’s still a fairly prevalent, little questioned practice in Western society— when you have a couple male friends, it does come up in conversation— and those who have been circumcised are typically non-religious white guys, despite it being an historically Semitic custom. Certain things are accepted into Western society and thus ignored.

Often, re-printed books that made an impact will publish with new prefaces and introductions, and I tend to read these after I’ve finished the main story. I do this because I like to know what my mind’s original path through a text is, before I lock in to critically reflect. I can track my own prejudices, or preoccupations this way.

For example, a preoccupation that I had was on women resolving to do sex work in order to survive. This is because sex work is of critical interest to me, but I go into the text not looking for any particular answer; I’m curious just to see what is there. Firdaus does not simply walk herself into a brothel and ask for a job— she is in a truly destitute, vulnerable position when she becomes a prostitute. El Saadawi makes a clear argument as to the distinct, systemic abuses that make sex work so problematic:

A policeman says,

“You’re a prostitute, and it’s my duty to arrest you, and others of your kind. To clean up the country, and protect respectable families from the likes of you. But I don’t want to use force. Perhaps we can agree quietly without a fuss. I’ll give you a pound: a whole pound. What do you say to that?” (p. 74).

The hypocrisy not just of man but of manmade system as a whole is revealed here. This, explicitly, is what patriarchy enables, while disabling a woman of such low status the agency to control the outcome of her situation. The security that could protect Firdaus from this trap is entirely absent, because it comes in the form of money and family, neither of which she has; both would insure her life, to some degree, from total destitution. That she has neither is no fault of her person, and we know this as we read, but one can sense the precariously low social standing— how bad she looks in the eyes of society— she has as a result. The important detail to take from here is that class plays as much of a damning role as gender.

It is not that Firdaus is female in isolation from all else, that she suffers so much. It is just as vital to think about the other constructions at play that have steered her life trajectory for the worst. Her being female obviously is an important factor, but it should not be overblown to the point of vilifying all Arab men. In the very last few pages of Firdaus’ story, when her sense of self becomes its most hardened and brutal, she admits that she “became aware of the fact that [she] hated men” (p. 106). If you’re male, this is a tough thing to read. The takeaway here, though, is not that men are inherently bad (hateable), but that one, after hearing her life story, should empathise with what the accumulation of her experience has taught her.

Other criticisms towards El Saadawi are levelled at her literary merit. I acquiesce that her writing is not especially literary— it is sparse in description, simple, at times the dialogue feels stiff. But El Saadawi’s goal is to express a point, a position. She is effectively making a polemic. It’s not easy to stomach, when you get to the end, but it’s worth really thinking about.

There is a great deal of interesting paraphernalia to be found in Woman at Point Zero if you really look. Vigilance while reading is important, and of course, not everyone wants their reading to be so active. You’re going to take things away, though, whether you do so consciously or not. Your reading becomes a part of the production.

Paralleled loves / the teacher, the revolutionary

It becomes so dark, so bleak by the end, that it’s easy to forget that Firdaus experienced two moments of aching, vulnerable hope. The first is when Firdaus becomes attached to her teacher, Miss Iqbal, in high school. The second is with the revolutionary man at the factory she works, Ibrahim.

Both these moments in the text mimic each other. At first, when I reached the second moment, I thought, this is weird. I think most of us will agree that people don’t experience their individual moments of falling in love in quite the same ways, let alone the exact same thoughts, word for word. However, this explicit crafting allows us to contrast. The distinction between the first and second instance is that Firdaus’ infatuation with Ibrahim fits readily into the social convention of heterosexuality. The love itself is not questioned, instead it is the classes of the people involved. When Firdaus falls in love with Miss Iqbal, it is not made explicit that this is what is actually happening; it seems purposely abstract, as appropriate for a love that doesn’t fit into any romantic convention Firdaus understands.

“The feeling of our hands touching was strange, sudden. It was a feeling that made my body tremble with a deep distant pleasure, more distant than the age of my remembered life, deeper than the consciousness I had carried with me throughout” (p. 34).

The quote above, when you see that the “distant pleasure” is linked to her severed clitoris— and thus the ability to feel much sexual arousal— makes this moment of love for Miss Iqbal all the more heartbreaking, and doubly confusing for Firdaus. The genital mutilation becomes a symbol for the loves that are entirely lost, unable to be realised and embraced. This quote is also repeated, word for word, when Firdaus experiences the same (crafted) moment with Ibrahim, later in her life. It also brings us back to this yearning for romantic understanding, but further, it acts to recall us to Miss Iqbal.

The ultimate break between these two instances is made clear when you refer back to Miss Iqbal, and Firdaus telling her friend, “But she’s a woman. How could I be in love with a woman?” After this is uttered, it is probed no further. How could she? No one around her knows, no one can help her unravel it. In contrast, when she speaks to a coworker about her confused feelings for Ibrahim, this is the exchange:

“Ibrahim is a fine man, and a revolutionary.”

“I know. But I am no more than a minor employee. How could Ibrahim possibly fall in love with a poor girl like me?” (pg. 96).

Sex, gender, sexuality, and class are inextricable here. Moreover, though class presents itself as the obstacle (as opposed to having no understanding of homosexuality), in a less dark text, class is merely an aspect that raises stakes and thus romanticises the relationship all the more. We know Firdaus kills a man and is in prison, awaiting death. But we can’t help but wonder if this love eventuates for Firdaus— it certainly feels more feasible than the absent love between a teenage Firdaus and her young teacher.

I’ve already warned you that there’ll be spoilers, so, I don’t think it’s all that surprising that the relationship with Ibrahim is short-lived and breaks Firdaus’s heart. Somehow, I find myself mourning the relationship with Miss Iqbal far more. Ibrahim’s betrayal symbolises a revolutionary cause (hope) being a sham, but Miss Iqbal was a good teacher to Firdaus: when Firdaus has no family members to receive her awarding of the secondary school certificate it is Miss Iqbal who stands up and receives it for her. When Firdaus leaves the school for the last time, she hangs around in agitation, waiting for Miss Iqbal to appear. She doesn’t. But if only she had.

Resource

Amireh, A. (2000). Framing Nawal El Saadawi: Arab Feminism in a Transnational World. Signs, 26(1), 215–249.

Not me making myself emotional writing that last paragraph. MY GOD. I’m obviously HURT that Firdaus wanted to be educated so bad and her life was just so consistently NASTY. RAAAAAAAAA—

oh this review is so articulate!! I don't think I would like the book but I'm glad you shared your thoughts about it. it's so interesting and so tragic to think about "femaleness" being one of those things that, in a bad life, contributes to a worse one. you said something about how being female is something that is thrust upon you by society - it is scary to consider how inescapable and dangerous that society-identity can be. a female body in a vacuum is unremarkable. but a female body in a patriarchy can be... quite dangerous to have. and that is without even factoring in class, race, gender, sexuality, etc., like?? I hope that makes sense. I agree w u: RAAAA